You can cook fentanyl as easily as broth. Are we facing an epidemic? [OKO.press INVESTIGATION]

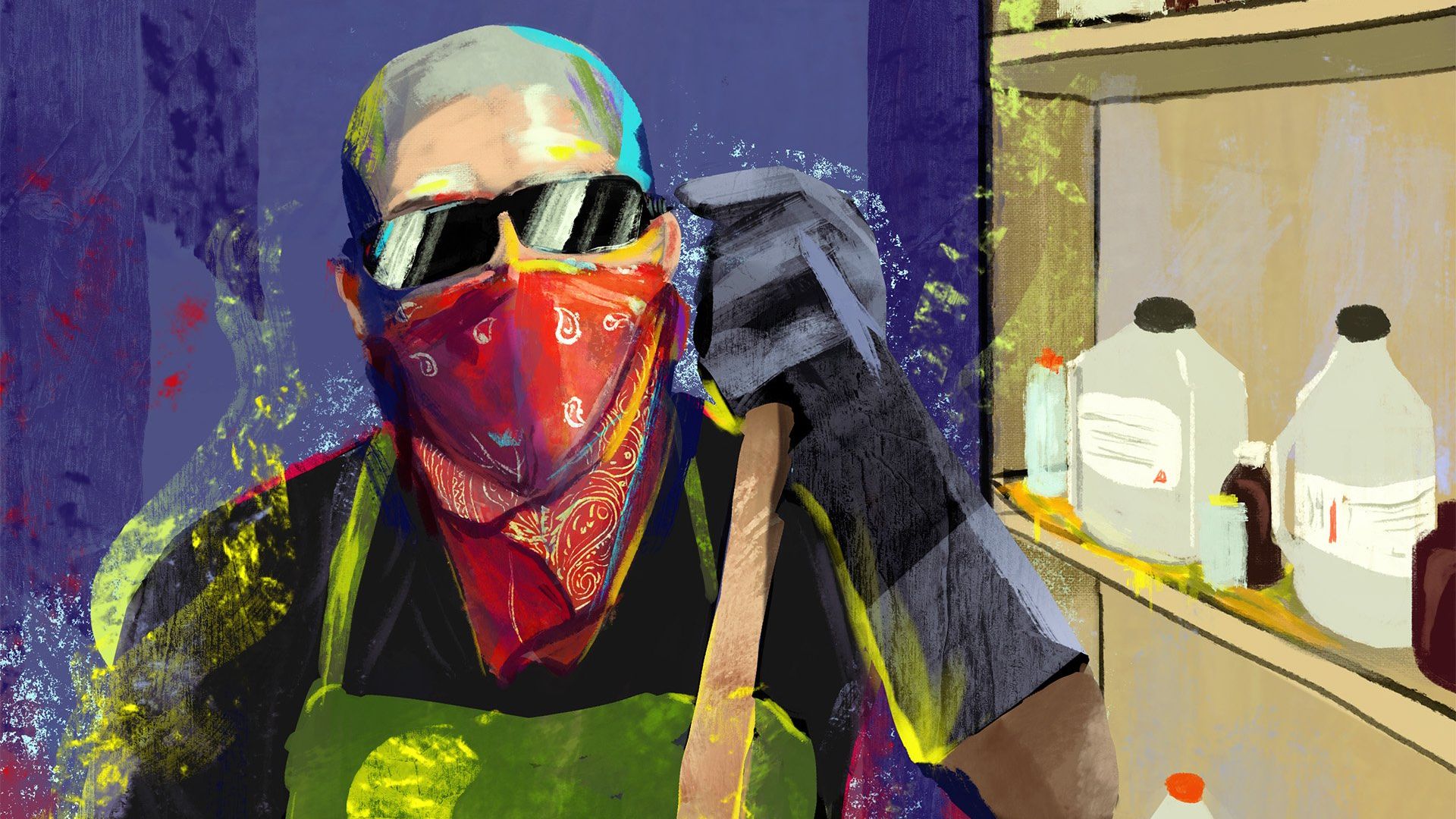

‘I pour this, I sprinkle that, and a dozen or so hours of cooking later I have a grey-white paste resembling dough.’ The cook talked as if he was dictating a recipe for guacamole. ‘We dry it in the sun, grind it into powder and pack into bags.’ ‘You are good at chemistry?’ ‘I don’t. What for?’

Powiedz nam, co myślisz o OKO.press! Weź udział w krótkiej, anonimowej ankiecie.

Przejdź do ankietyPublikujemy angielską wersję cyklu 4 reportaży Szymona Opryszka, które ukazały się w OKO.press.

Reporterskie śledztwo OKO.press. Pojechałem do Meksyku śladem sfałszowanych tabletek znanego leku z domieszką fentanylu. Mafia bałkańska miała je ściągnąć do Europy Wschodniej. Spotkałem się z kucharzem fentanylu w meksykańskim stanie Sinaloa. Nawiązałem kontakt ze sprzedawcami prekursorów tego narkotyku w Chinach. Rozmawiałem z afgańskimi rolnikami opium i wieloma ekspertami od rynku narkotyków i bezpieczeństwa publicznego.

W czteroodcinkowym śledztwie szukam odpowiedzi na pytanie: Czy Europie grozi kryzys fentanylu?

Przeczytaj także:

Poniżej angielska wersja 1 odcinka.

OKO.press reporter’s investigation. I went to Mexico looking for counterfeit tablets of a well-known drug with fentanyl mixed into it. The Balkan mafia was supposed to bring them into Eastern Europe. I met a fentanyl cook in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. I made contact with the sellers of this drug’s precursors in China. I talked to some Afghan opium farmers and many experts on the narcotics and public safety market.

In this four-part investigation, I look for answers to the question of: Is Europe under threat of a fentanyl crisis?

Below is the first part.

‘Do you know how to make caldo?’ Chucho surprised me.

He was waiting for me at the greengrocer’s and was scratching himself on his stomach. The greengrocer’s was in the outskirts of Culiacán, in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, where the most popular soup is ‘caldo de res.’ It’s a bit like broth cooked on beef bones with added potatoes, chayotes, pumpkin and corn. Fresh coriander and sour lime juice add aroma.

I had barely managed to say yes to Chucho, and we were already sitting on wooden crates at the back of the greengrocer’s. He wiped his hands on his dirty navy blue overalls, pulled a cigarette from his breast pocket and lit up.

‘Why is the broth so aromatic?’ he asked.

‘Is it the time it takes to be cooked?’ I hesitated.

‘It’s the spices! The proportions are key! Believe it or not, making fentanyl is easier than cooking caldo.’

How do you find the cook?

The greengrocer’s smelt of cut watermelon. Some customer was examining each quarter carefully, just like Chucho examined my passport. I don’t know why he agreed to being interviewed. Out of pride, curiosity, or perhaps a sense of impunity?

I wanted to meet a cocinero, that’s what fentanyl cooks are called in Mexico. I wondered if Europe was also under threat of a fentanyl crisis. I spent months talking to experts, reading reports, but I wanted to get a perspective from someone from the other side. Maybe see the laboratories and witness fentanyl being cooked?

I had worked with members of Mexican cartels before. For example, in Tijuana on the U.S. border, writing about the smuggling of migrants from Asia and Africa. But also about avocado plantations in the state of Michoacan. This is one of the most profitable ‘legal’ businesses of the cartels.

But I have never hit a brick wall as hard as I had now with fentanyl.

When all the proven methods had failed, I asked for help from Miguel Angel Vega, a renowned fixer in Mexico who specializes in organized crime. He told me to take a trip to Culiacán, a stronghold of the Sinaloa cartel. I didn’t know where I would meet the cocinero until the last minute.

When they called, I had fifteen minutes to get to the designated place. But I got lost among the empty warehouses, scrapyards and houses that had not been finished off for years, because the battery in my phone had died because of the heat. The satnav had stopped working. I had barely cooled my phone down when they called me to tell me to turn around and turn left. They must have been watching my grey car.

When I stood in front of a brick greengrocer’s surrounded by wooden crates, they told me to put my phone on the counter and talk. I explained that I had been working in Mexico a few months earlier on a report about so-called VIP migrants from the Caucasus and Central Asia, who were being smuggled into the U.S. by smugglers associated with the Sinaloa cartel. Some informant there mentioned that the Mexicans had entered into an agreement with the Balkan mafia and were smuggling counterfeit opioid tablets spiked with fentanyl, which is 50 times stronger than heroin, including Oxycodone, into Eastern Europe.

‘M30,’ Chucho interrupts me.

‘What?’

‘That’s what we call these tablets.’

Yellow, pink, blue, all the same shit

Chucho is 31 years old. He dropped out of school as a teenager and started working as the cartel’s ‘eyes and ears’.

Two years ago, he bought a Chinese pill press for a thousand dollars and now produces not only powdered fentanyl, but also pills, which are popular on the streets of American cities, namely ‘China Blanca’, ‘Apache’, ‘Dance Fever’, ‘He-Man’ and ‘Ivory King’.

At least a dozen cartels in Mexico produce fentanyl, the most active being Sinaloa and the cartel from Jalisco. The specialist InSight Crime website estimates that synthetic drug producers in Mexico produce as much as 4.5 tons of pure fentanyl a year for the U.S. market alone. Some, who look for new markets, try to reproduce prescription drugs that are sold in Western countries. They are known as M30 because of their weight. This is how they reach people who are looking for cheaper substitutes of drugs. Many of them have no idea that the pills contain fentanyl.

‘We dye them yellow, pink or blue, but it’s all the same shit.’

‘Why do you dye them?’

‘Marketing. Women prefer yellow ones. Homos want pink ones...’

‘Do you also ship them to Europe?’

‘We cook them, sell them and ship them. But where? ‘I won’t tell you.’

‘Why?’

‘Do you know what goes on in town?’

Did Los Chapitos betray El Mayo?

Indeed, Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa, was sizzling like a hot wok.

A month before our meeting, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that the Ismael ‘El Mayo’ Zambada, who had been wanted for a long time, had been arrested. ‘El Mayo’ and Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the famous ‘El Chapo’, set up a cartel that had expanded in this agricultural state and dominated the global narcotics market in the 21st century.

In 2017, after two spectacular escapes from Mexican prisons, ‘El Chapo’ was caught and extradited to the U.S. Two years later, a New York court sentenced him to life imprisonment.

‘El Mayo’ and ‘El Chapo’s’ four sons, the so-called Los Chapitos, continued to expand the empire. They focused on the lucrative fentanyl and expanded the cartel’s operations into Asia, the Middle East, Australia and Europe. They also took over many of the country’s legal businesses, from logging to fisheries, mining and water management.

‘El Mayo’, who avoided publicity, and ‘El Chapo’s’ brutal sons divided their influence. ‘This structure theoretically allows the heads of independent drug trafficking groups to share resources — such as smuggling routes, corrupt contacts, access to illegal chemical suppliers and money-laundering networks,’ reads a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) report. In short, the factions cooperate in some areas, but they do not share profits and do not answer to a main chain of command.

Perhaps it’s a simple generational conflict, perhaps increasing pressure from the Americans, perhaps competitors from the Jalisco Nueva Generacion cartel, who are growing in strength, or perhaps all of these together?

When the Mexican army arrested Ovidio, ‘El Chapo’s’ son, a year ago, the rest of the young faction believed that their father’s old friend had set up their brother. So, when ‘El Mayo’ was captured in July and flown to the U.S. by the U.S. services, a rumor quickly spread in Sinaloa that Los Chapitos were behind this ambush.

The spectre of the cartel’s disintegration hung over Culiacán. Revenge was in the air. The streets were empty, schools were closed and many shop windows were locked shut.

Chucho was waiting for events to unfold and happily chewed gum that coloured his tongue blue.

More murders than days in a year

‘What if they were to call to tell you to go to the laboratory?’

‘I would go to the shop.’

‘What for?’

‘For milk. When I go up into the mountains, I take two or three litres with me.’

‘Of milk?’

‘Well, yes!’

‘What for?’

‘The stench in the laboratory makes me want to throw up. I had some colleagues in the kitchen who didn’t wear masks and ended up like addicted zombies. Or with burning wounds because they were cooking in short sleeves instead of tight suits. But me? Seven years and still healthy, all thanks to milk.’

‘Thanks to milk?’ I thought this was some sort of slang abbreviation. I couldn’t shake off the feeling that words have different meanings in Culiacán. After all, I was sitting with the ‘cook’ and the ‘owner of the greengrocer’s’, discussing ‘broth’. All my previous interviewees referred to narcotraficantes as ‘those people’. They frequently simply said ‘they’.

A famous professor from the Autonomous University of Sinaloa refused to give me an interview because of ‘the latest situations’. While the receptionist in a destroyed hotel wished me the avoidance of ‘events’.

Perhaps I was trying too hard to find a literal meaning? Like when I saw a big sign opposite the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary that read ‘Cuidado,’ namely ‘Beware.’ When I crossed the street, it turned out to be just a part of the name of a popular clothing brand.

A local journalist told me that they have to survive more murders in Culiacán than there are days in a year. According to data from the state prosecutor’s office, there was only one year in the last seven (2022) that the number of so-called ‘intentional homicides’ was less than five hundred — 499 to be precise.

Words only regain their meanings in epitaphs. Crosses by the roadside, memorials hanging on trees, small monuments decorated with fluffy animals are like open wounds. Simply put, they commemorate the victims where they were executed: in ditches, on pavements, in side streets.

You go shopping at the City Club shopping centre, and there is an obelisk in the middle of the car park. This is in honour of ‘El Chapo’s’ son, who was murdered there in 2008. The funeral was on Mother’s Day, but ‘El Chapo’ ordered all the red roses in town to be bought up. The tombstone overlooking the tyre repair garage bends under the weight of flowers on every anniversary to this day. And they never wither in the guarded Jardines de Humaya cemetery either.

I didn’t risk paying a visit, but even TikTok shows how the drug barons and hit men are buried in air-conditioned mausoleums with marble floors, satellite TV and wi-fi. These are probably the most expensive properties in the ‘city of crosses’, as Culiacán is sometimes called.

My doubts only made Chucho lose his cool.

‘Milk! I drink normal milk,’ he ended the discussion. ‘The kind from a cow. Mooo!’

A tarpaulin covered hut

Customers were milling around by the greengrocer’s counter. Some neighbour was picking out limes and peering curiously into the back of the store. Old women were complaining about the prices. A little girl ran in for avocados because her mother had run out. The shopkeeper greeted everyone and signalled to us to speak more quietly.

‘So what would we need?’ I tried to tear Chucho away from the phone.

‘For what?’

‘You know, to make broth,’ I drew quotation marks with my fingers.

Chucho lit up another cigarette and gave a phone with photographs of the laboratory where he had recently been managing a group of twelve cooks. A small hut covered with a tarpaulin, hidden under branches and camouflage netting. Large gas canisters with huge burners stood under a tree, while empty canisters and barrels labelled ‘Pure acetone’, ‘Fentanyl XXX’ and ‘Chemicals from China’ in Spanish and English were scattered around.

One-pot method

The most popular method of producing the illegal narcotic is the synthesis of fentanyl analogues using the Gupta method. This method is named after Dr Pradeep Kumar Gupta, a chemist from India who invented it. It is also called the ‘one-pot method’, because the synthesis is carried out in a single reaction vessel. Meanwhile, the Mexican cocineros have developed their own, highly simplified version of this technique and do not need specialist laboratory equipment.

‘I pour this into the pots,’ the cook pointed to a photograph of the barrels with the word chlorine on them. ‘Two fingers deep, no more. Then I mix it with this yellowish and toxic liquid from China.’

‘What’s it called?’

‘I can’t remember the names,’ Chucho surprised me. Then the greengrocer’s boss sent me a ‘shopping list’ by text message, which included acetone, caustic soda, arsenic trioxide, sodium bicarbonate and precursors known as NPP and 4aNPP, produced industrially in Chinese and Indian laboratories.

‘So I pour this and sprinkle that, and after a dozen or so hours of cooking I have grey-white paste that resembles dough,’ the cook spoke as if he was dictating a recipe for guacamole to me. ‘We then dry it in the sun, grind it into powder and pack it into bags. And that’s the whole deal.’

‘How do you know chemistry?’

‘I don’t. What for? They once sent us a chemistry student. She was well-versed in theory, but when she saw the laboratory, she panicked. She wanted to see the recipe. She didn’t believe we were cooking by smell.’

‘I don’t believe it either,’ I blurted out, but then the greengrocer’s boss, with wrinkles on his head, thanks to whom I met Chucho, joined in. He had so far only been listening to the conversation or grunted a little when tomatoes were flying out of the shop assistant’s hands.

‘Do you know who you’re talking to?’ he warned me. ‘Why do you need these damned recipes? Take this aguachile, our local classic made of shrimp and raw fish. Have you ever tried it? How long should shrimps be kept in the marinade? How much lime juice should be squeezed in? What can you get away with when putting in chiltepin peppers? You’ll only find out by trial and error. So listen to the king of cooks, he knows what he’s talking about.’

Clearly flattered, Chucho took another drag on his cigarette. He cupped the imaginary aluminium foil in his hands, made a gesture as if he were sprinkling it with powder, then brought the lighter closer and lit it.

‘After seven years in the kitchen, you know that if you haven’t screwed up, you’ll detect a delicate smell of burnt popcorn. That’s the sign of quality.’

This is, after all, just a fairy tale for Americans

People like Chucho work in primitive laboratories hidden high in the mountains northeast of Culiacán or in the swampy mangrove forests on the Pacific coast. When he started seven years ago, he was promoted from ‘eyes and ears’ to ‘frying pan cleaner.’ Frying pans are large pots in which the fentanyl preparation is made. Such ‘kitchens’ with cooking utensils placed on pallets can be built quickly and cheaply. And if they are found out, they can be demolished, abandoned or moved to a safer place.

A year ago, president Andrés Manuel López, whose office was ending, argued that Mexico had nothing to do with fentanyl production. Even though, during his six-year term of office, the army liquidated 2,132 synthetic drug laboratories, mainly methamphetamine. All under pressure from the Joe Biden administration.

Last year alone, the fentanyl crisis claimed over 70,000 victims in the U.S. The Democrats needed successes in the fight against the cartels that send both fentanyl and migrants from Mexico – after all, these are two key topics in the debate leading up to the forthcoming presidential elections.

In 2023, Mexico confiscated a record quantity of over 2,300 kilograms of fentanyl, which is over twelve times more than two years earlier. But the data from the U.S. is more reliable: during the same period, the Americans seized 80 million fake pills with fentanyl add-on and over 5 tons of pure powder. That’s the equivalent of 390 million lethal doses.

As soon as I mentioned these statistics, Chucho smiled with pity.

‘The politicians say what people want to hear.’

‘Namely?’

‘They always lie. The gringos from the DEA are the most deceitful dogs. They can talk about confiscations. But I know better. A few days in the mountains are enough for me to produce a million pills.’

‘What about the prohibitions?’ I dropped in. I meant narcomantas, or the cartel’s ‘parish announcements’. ‘The sale, production, transport or any other activity related to fentanyl is strictly prohibited in the state of Sinaloa, as is the sale of the chemicals used to produce it,’ announced ‘El Chapo’s’ sons on banners that were hanging in Culiacán last year. Sooner or later, this type of narco-message reaches everyone, especially when it ends like this: ‘You have been warned. With all due respect, Los Chapitos.’

‘Do you believe that? This is, after all, a fairy tale for Americans!’ smiled the manager of the greengrocer’s. ‘You know, various customers come to me. Their grandfathers cultivated opium, their fathers transported coke, and they cook fentanyl. Do you think anyone would give that up?’

A bag will make you a millionaire

The relay of generations in the state of Sinaloa started a hundred years ago, when Chinese immigrants established the first opium plantations here. Mexican farmers soon took over and, during the Second World War, they were producing opium with the consent, and even encouragement, of the U.S. authorities, because the Allied hospitals needed morphine and heroin.

In the following decades, the region became a global supplier of marijuana, and in the 1990s, after the Colombian gangs were disbanded, the Mexicans took control of the cocaine routes.

When the legalization of marijuana reduced demand, the Sinaloa cartel outpaced market demand and produced tons of heroin and methamphetamine. Synthetic drugs, mainly fentanyl, have recently become the hit.

I read in a Rand Corporation think tank report that the opium needed to produce a kilogram of heroin can cost producers approximately $6,000. The Chinese chemical precursors needed to produce fentanyl cost about $200–$300 on the black market. While thousands of doses can be made from a kilogram of pure fentanyl – the further away from the laboratories, the higher the price.

‘Production is not only profitable, but is also easier than, for example, heroin,’ the shopkeeper continued. Throughout the meeting, we pretended that I had no idea that he was the coordinator of the cooks in Culiacán. (I heard about this from my informer).

‘Why?’

‘You don’t need large areas of land to grow poppies, which make it easier to catch you. You don’t worry about the crops. Well, and you don’t have to pay farmers, like me, a poor carrot seller? In other words, you only have profits.’

One bag can make you a millionaire. But you have to share the profits. The bosses, obviously, take the most. The cooks, packers, drivers, and finally the smugglers are given a small percentage. Large enough for the conditions of the extremely unequal Mexico.

The pauper and the one in the armoured car

Mexico is one of three countries in the world, alongside Mozambique and the Central African Republic, where all wealth is concentrated in the hands of one percent of the population.

Such a scene in the capital of Mexico: a guy in an armoured car tries to drive through a crossroads, but a pepenadores’ cart has turned over in the middle of the street. They are garbage sorters; during the day they travel through the city in search of waste and at night they return to tin huts beside huge landfills. They live without running water or sewage, on the equivalent of $1.50 a day. The rich guy shouts out from the car, but when one of the pepenadores looks up, he meekly closes the window. The pepenadores lower their eyes but do not move aside. Both parties are paralyzed with fear.

Inequality drives this business: one armoured car is sold every two and a half hours in Mexico. The rich pay for private education, healthcare, garbage collection systems, water, but also an army of security guards. Nationally, spending on private security is seven times higher than spending on public safety. And, after all, security guards earn an average of just $250 a month and can work as much as 60 hours a week. In fact, Mexicans are among the longest-working societies in the world. Which does not necessarily mean breaking out of poverty, in which as many as 46.8 million people live here (36 out of 100 people).

Poverty on the surface, wealth in complete isolation – researchers call this system the ‘matryoshka society’.

My light aircraft

‘Chucho, do you ever think about these people?’

‘Which people?’

‘The fentanyl victims.’

‘No.’

‘Don’t you have any remorse?’

‘Never.’

‘So what do you think about?’

‘About money. I like money.’

‘Is it worth risking so much for it?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Do you feel rich?’

‘I’m not a millionaire.’

‘How much do you earn?’

‘They used to pay as much as $3,500 per kilogram. Today, they pay between $1,000 and $1,500. It depends on the size of the order.’

‘So what have you bought for yourself recently?’

‘What do you have in mind?’

‘Some clothes? A computer? A car?’

‘A light aircraft.’

* The report was prepared as a result of the cooperation with Mexican fixer Miguel Angel Vega, whom I would like to thank for his advice and help on site.

* The main character’s nickname and certain facts have been changed for safety reasons.

Sources:

- Complexities and conveniences in the international drug trade: the involvement of Mexican criminal actors in the EU drug market, Europol, 2022, https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Europol_DEA_Joint_Report.pdf

- Ruggero Scaturro, Walter Kemp, ‘Portholes. Exploring the maritime Balkan routes’, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GITOC-SEE-Obs-Portholes-Exploring-the-maritime-Balkan-routes.pdf

- Relazione Annuale 2023, Italy’s Ministry Internal Affairs, https://antidroga.interno.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Relazione-Annuale-2023-dati-2022.pdf

- Felbab-Brown, The foreign policies of the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG – Part V: Europe’s supercoke and on-the-horizon issues and the Middle East, 21/09/22, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-foreign-policies-of-the-sinaloa-cartel-and-cjng-part-v-europes-supercoke-and-on-the-horizon-issues-and-the-middle-east/

- Felbab-Brown, The foreign policies of the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG – Part IV: Europe’s cocaine and meth markets, 02/09/22, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-foreign-policies-of-the-sinaloa-cartel-and-cjng-part-iv-europes-cocaine-and-meth-markets

- Soto Rodríguez, ‘Fentanilo, el gran negocio del crimen organizado: implicaciones en el combate a las Drogas’ Revista De Relaciones Internacionales De La UNAM, 2022, https://revistas.unam.mx/index.php/rri/article/view/83040

- Dalby, ‘El flujo de precursores químicos para la producción de drogas sintéticas en México’, insightcrime.org, May 2023, https://insightcrime.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/El-flujo-de-precursores-quimicos-para-la-produccion-de-drogas-sinteticas-en-Mexico-InSight-Crime-May-2023.pdf

- ‘México libra una “guerra imaginaria” contra las drogas con redadas a laboratorios inactivos’, El Economista, 21/12/23, https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/Mexico-libra-una-guerra-imaginaria-contra-las-drogas-con-redadas-a-laboratorios-inactivos-20231221-0018.html

- Quirós, Real Instituto Elcano, Cárteles mexicanos en el mercado europeo de drogas sintéticas: alcances y lecciones desde la pandemia de SARS-CoV2, 11/06/20, https://media.realinstitutoelcano.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ari84-2020-quiros-carteles-mexicanos-mercado-europeo-drogas-sinteticas-alcances-lecciones-pandemia-sars-cov2.pdf

- Farah, ‘Fourth Transnational Criminal Wave: New Extra Regional Actors and Shifting Markets Transform Latin America’s Illicit Economies and Transnational Organized Crime Alliances’, International Coalition Against Illicit Economies, 2024, https://icaie.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ICAIE-DF-Authored-Fourth-Transnational-Criminal-Wave_-New-Extra-Regional-Actors-and.pdf

- Singer, Europe Braces for a Surge in Black Market Synthetic Opioids, Cato Institute, 23/07/24, https://www.cato.org/blog/europe-braces-surge-black-market-synthetic-opioids

- Balkan cartel trafficking cocaine around the globe in private planes busted, https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/balkan-cartel-trafficking-cocaine-around-globe-in-private-planes-busted

- Martínez-Oró, ‘Fentanilo en España. Evidencias, percepciones y realidades’, Episteme Investigacion e intervencion social, 2024, https://www.epistemesocial.org/wp-content/uploads/Fentanilo-en-Espana.-Evidencias-percepciones-y-realidades_web.pdf

- Martinez, En qué países de África opera el Cártel de Sinaloa, 09/02/2024, https://www.infobae.com/mexico/2024/02/09/en-que-paises-de-africa-opera-el-cartel-de-sinaloa/

- Cardoso, ‘The Cartel’s Colour’, Small Wars Journal, 09/06/2019, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/cartels-colour

- ‘La transición hacia el fentanilo: Cambios y continuidades del mercado de drogas en México (2015–2022)’, Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 36(53), 15–36, 2023, https://doi.org/10.26489/rvs.v36i53.1

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2024, DEA https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2024-05/NDTA_2024.pdf

This article has been produced with the support of Journalismfund Europe

This report was produced with the support of the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation

Reporter, absolwent Polskiej Szkoły Reportażu i Szkoły Ekopoetyki. Pisze na temat praw człowieka, kryzysu klimatycznego i migracji. Za cykl reportaży „Moja zbrodnia, to mój paszport” nagrodzony w 2021 roku Piórem Nadziei Amnesty International. Jako reporter pracował w Afryce, na Kaukazie i Ameryce Łacińskiej. Autor książki reporterskiej „Woda. Historia pewnego porwania”, (Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 2023). Wspólnie z Marią Hawranek wydał książki „Tańczymy już tylko w Zaduszki” (Wydawnictwo Znak, 2016) oraz „Wyhoduj sobie wolność” (Wydawnictwo Czarne, 2018). Mieszka w Krakowie.

Reporter, absolwent Polskiej Szkoły Reportażu i Szkoły Ekopoetyki. Pisze na temat praw człowieka, kryzysu klimatycznego i migracji. Za cykl reportaży „Moja zbrodnia, to mój paszport” nagrodzony w 2021 roku Piórem Nadziei Amnesty International. Jako reporter pracował w Afryce, na Kaukazie i Ameryce Łacińskiej. Autor książki reporterskiej „Woda. Historia pewnego porwania”, (Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 2023). Wspólnie z Marią Hawranek wydał książki „Tańczymy już tylko w Zaduszki” (Wydawnictwo Znak, 2016) oraz „Wyhoduj sobie wolność” (Wydawnictwo Czarne, 2018). Mieszka w Krakowie.

Komentarze