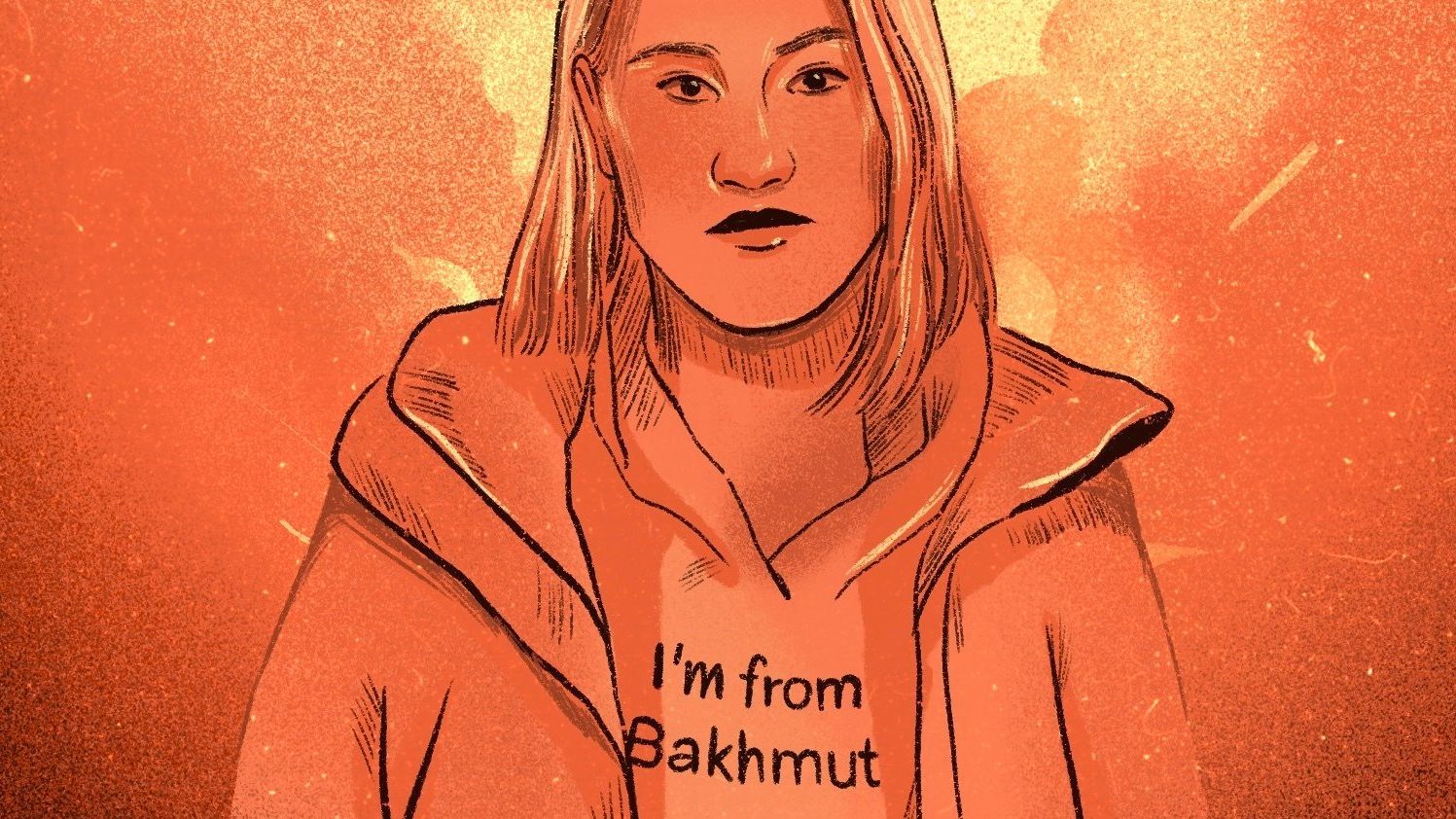

I’m from Bakhmut, my husband is fighting on the front line today. I’m waiting for him to call

A minute of life in Bakhmut is worth 17 zlotys. Kostya’s monthly salary, with the war allowance, is almost 4800 zlotys after conversion. The government is paying an additional 100,000 hryvnias, or 12,500 zlotys for every month on the front. That is PLN 416 per day in hell. Days of pay are deducted for every day in hospital [REPORTAGE]

Powiedz nam, co myślisz o OKO.press! Weź udział w krótkiej, anonimowej ankiecie.

Przejdź do ankietyTekst Kingi Gałuszki "Jestem z Bachmutu, mąż walczy dziś na pierwszej linii. Czekam aż zadzwoni" opublikowaliśmy 23 marca 2023 r.

There will be a cake this year. A big and very sweet one. Everything is ready for Tioma's fifth birthday. Only Kostya has not called yet. His phone is still out of reach. He was supposed to call in the morning, it’s just eleven o'clock, it’s not so bad. That means he hasn’t returned to base as planned, even though he has been in position for three days. In position means in the abandoned houses of Bakhmut that has been levelled to the ground, which the Ukrainian soldiers are defending against the Russians. And they are not allowing themselves to be killed. In position, one, two days of rest, in position, and here we go again.

Knife

Ira and her son leave for Poland on 8 March last year. It is still difficult to believe, but this is the second week of the war. They have travelled three hundred kilometres, four days in the car and a sigh of relief that this is it. Meanwhile, a sense of unreality still holds strongly. How is it that they are just twenty metres further and the war is not sitting on their bumper? The day before, at some stage of the twenty-four-hour queue at the border in Hrushiv, Tioma turns four. Ira tells him nothing. There is a toy at the petrol station shop, which the child – like every other his age – wants here and now. But he cannot, because who knows what expenses are awaiting his mother in a foreign country.

Our sons end up in the same group in a Warsaw nursery school. This is how we meet each other. Ira comes from Bakhmut in the east of Ukraine. Everyone has already heard about this place, where the heaviest fighting of this war has been going on for months. Ira’s husband has been serving there since January.

One hundred and forty-four hours. Six days – that’s the longest he has not been in touch. If the worst happens, the family is notified rather quickly. Provided that the body can be easily recognized. In Kostya’s unit, he is responsible for that. Like when he had to identify a mate whose face had been ripped off. He only managed to do so when he found a knife that his mate had once shown him. It took a while, even though the body was lying right next to him. So the phone call to his nearest and dearest was also delayed. How long could it have been? More than a day?

Shashlik

So it’s going to be a cold cheesecake. The recipe is quite simple. First you have to make a solid base – chop up twenty-four Oreo biscuits, just remove the cream from the middle, set it aside and add melted butter. By the time the crumbs combine well, you already know from the media that things are now very difficult. The internet scares readers that it is becoming worse every day, with direct fighting on the streets of Bakhmut. Apparently the Russians today encircled the Ukrainian army and penetrated its side. Someone posted such information to Ira in one of the chat rooms a moment ago.

Moments later, however, Ira comes across a photograph showing that, for the time being, the Rusina, as the Ukrainians pejoratively call the Russians, have only bombed the famous MiG-17 monument.

Ira does not move anywhere without a powerbank; she charges her phone twice a day. The battery also has to face the gigabytes of this war.

They talk to Kostya or just look at each other whenever his phone is within the range of the network. The interruptions have been more frequent since he has been on the first front line. There is no electricity, gas or water in Bakhmut, or, all the more so, internet.

Only later, when he returns to base from his position, does he tell her where he has been. Never directly. Instead, he says: today we went to where our wedding was. It is clear – it is a restaurant called ‘Shashlik’ in the centre of Bakhmut.

About a month ago, he sent her a video of himself and the mates from his squad patrolling ulitsa Mira, in the centre of Bakhmut. Laughter can be heard: ‘Here’s a video of a scary city. Some fool is going for a walk. And unfortunately it’s me.’

The backs of several armed non-actors can be seen on either side of this non-scenery, a deserted city and destroyed buildings can be seen, glass can be heard crackling under the shoes, the trolleybus lines are hanging above their heads. They pass a music school, an Artwinery shop, a Bakhmut champagne plant, some trenches, a coordination centre, once a police and border guard base, a stately Martynova Centre of Leisure and Culture. As Ira now flips through the photographs which people exchange in the chat rooms, it’s different now.

The school – gone.

The shop – gone.

The ‘shashlik’ – also gone.

But all this really was there. Just yesterday.

The Centre of Culture – they also burnt down that stately, classical building. I am weeping all day long because of the last of these, as you weep over a place that was a second home. She spent every moment of her spare time there for eleven years, dancing with the contemporary dance group. In the meantime, there were concerts, friendships, loves and first cigarettes somewhere in the halls, corridors and just around the corner. Five years ago, she danced with the girls from her group at the 30th anniversary of the dance club. They were arranging to meet up for the 35th anniversary. It was supposed to be in May this year.

Is it this anniversary or isn’t it?

Przeczytaj także:

Champagne

In December, even before Kostya is taken to Bakhmut, Ira also finds this picture: four soldiers are sitting on a couch. Someone who uploaded the picture to the Internet attached yellow smileys to them, so that they would not be recognizable, but they can still be seen to have big smiles on their faces. Well, these are ours. The frame is narrow, but it’s easy to see where the sofa is situated. Especially if this is your brother’s living room. I wonder if they’d go into their own living rooms with those boots as well. At least she knows the house is standing.

It’s already destroyed in the photographs he sees in February. Neither the sofa nor the brand-new mattress on which they put their feet are there anymore.

Two days earlier, she comes across a video from Artwinery, which had a shop in the centre of Bakhmut. It is a huge plant of the traditionally produced top quality bubbly, which was never exported to Poland. It’s dark, but the Rusnia can be seen loading successive cartons of wine onto a truck. Someone is laughing, waving at the camera and spray-painting the side of the truck: 8 March. Women’s Day without women with stolen champagne – what more could you want

Ira knows everything about wine from Bakhmut. She worked at the plant for five years as a tour guide. She took visitors to the cellars, where the wines were being aged for as long as five years, and told them what the millions of bottles held. Today I listen: brut – champagne made from Crimean material – the best and her favourite, brut muscat – very difficult to produce – and brut rosé.

She met a girl from Zaporizhzhia in Warsaw, all in tears after the shelling of that city. ‘It’s been like that with us every day for six months,’ she tells her. The other girl does npt know anything. Either that it is so bad, or even where Bakhmut is.

In the autumn, after the Russians once again bombed Kyiv, someone posted a picture on Instagram of a crater from an explosion in a playground, and a caption that our children will have nowhere to play. Ira is crying because of the bombs there and is getting angry. They should go round the corner and find another playground. The children of Bakhmut have nothing left. Neither a home nor a future. No one is crying over that city yet, and certainly no one ever weeps over eastern Ukraine.

Only when Zelenski mentions what is happening in Bakhmut in the U.S. Congress that people suddenly take an interest. In December 2022! Who careas that they have been bombing this city non-stop since August? But the truth is that Ukrainians themselves, especially those from the western part, find it difficult to imagine this city.

He then asks: ‘Do you know Artemovsky champagne? It’s from there.’ Everyone knows it and everyone drinks it, because there is none better.

Not like the shmurdzhiak from Odessa. Ukrainian shops still have some wines from Artwinery, There will not be any more because the factory is gone.

Zabakhmutka

The base of the cake is easy to form, you only need to knead the cake mixture in the cake tin and wait a bit for it to dry. Then soak the jelly in ice water and beat the curd, sugar and cream until fluffy. The smell alone is enough to eat.

Since 2014, the mayor of the time, Oleksiy Reva, has been planting roses in Bakhmut, whole rose avenues. They are literally everywhere. People are laughing that the mayor probably has a plantation and is selling them to the city at a higher price. They are renovating schools, nursery schools, renewing the square by the river, repairing the road to Kostiantynivka, then to Kharkiv, they are insulating houses.

Whoever lives in a small town knows that there is sometimes nothing to do. The young people are leaving to study in Kharkiv, 200 km away. She too, returns because of some stupid love that ends badly. She meets Kostya in 2015; he is here with his border guard unit. After all, after 2015, many soldiers come to Bakhmut, with their whole families, they fall in love with the place. Kostya first falls in love with Ira. They get married and live here together for eight years. A son is born to them here.

They enjoy walks along the Bakhmutka River, which flows through the middle of the city. It divides it into two parts. Ira goes on dates with Kostya by walking from Zabakhmutka, the part of city in the direction of Soledar and Popasna, where the family house is standing and the older brothers are living. There is also a winery there. The centre of Bakhmut, with the stadium and the school for Olympic staff established by Sergei Bubka, and the Centre of Culture, then there is Rose Alley, after which there is the New District, where she lived with Kostya, and right next to that was the aeroplane with which everyone in Bakhmut takes a selfie.

There is also a meat factory on that side: ‘Where do you live? Na miasie’ [on the meat], say the people in that area. Every part has a name: Sabachovka, Kvadratiy... In text messages with friends they type emoticons instead of names: Zabakhmutka – is a champagne bottle, Rose Alley – a flower … It is immediately clear where they will be drinking champagne tonight.

So far, the party is at its best in Zabakhmutka. Only the guests have gate crashed. A large roof of a large building can be seen in the dropne’s footage, which looks like a music video; everything in the background has been demolished, the landscape looks like it is from the apocalypse. On the roof, four Wagnerians are playing instruments, waving flags and dancing. Ira says this is her parents’ block, further away is the school she went to. The whole of their Zabakhmutka is now under the control of the Russians.

Tioma

The cottage cheese mixture should be beaten well, so it is smooth. When it is ready, it is time to heat the cream and dissolve the jelly in it. You have to be careful that lumps do not arise.

The recipe for the cake is written in Russian. Ira had Ukrainian at school. When they address her in Ukrainian, she answers in the same way. But at home they spoke Russian, as they did everywhere in the area and as has always been the case in eastern Ukraine; nobody is guilty here.

Three weeks ago, some woman on the metro in Warsaw makes some room for a child to sit next to her. Tioma does not want to sit down. Why is he so shy, asks the woman in Ukrainian. The little one asks Ira in Russian if he can talk to her at all. They then talked the whole way through by themselves. But there are also times, like literally moments later at the lift. Another woman hears them talking in Russian. She asks the child something in Ukrainian. ‘Why don’t you understand? Are you Russians?!’.

It is 24 February, the anniversary of the war, blue and yellow flags are everywhere. The child jumps for joy, seeing how many there are.

Or in the Polish clinic, where they also teach her what it is to be Ukrainian. A girl and her mother are waiting in line, it is noisy and crowded, Ira seems to be speaking in Polish. The little girl is even playing with the tags on Ira’s backpack, in the colours of the Ukrainian flag, and asks her something. Ira cannot hear and, in broken Polish, apologises for not knowing how to speak Polish. ‘You’re from Ukraine and you don’t understand Ukrainian?’ asks the little girl’s mother. Ira tries to explain that she did not hear. The woman does not say a word to her.

Sometimes, she thinks that perhaps those who are so outraged by her Russian have come, for example, from Ternopil. Or from some other city not affected by the war and they simply do not know that soldiers who speak various languages, including Russian, are fighting for them there in Bakhmut. There, with no regrets, but here, scolding. Let them go and let them lecture to Kostya or to those who died for them all.

Both here in Poland and in Ukraine, people like her, from eastern Ukraine, hear that they are not their own because they speak Russian. Nothing but waiting for the Russkies. Even if they are fleeing from them and the war, from their demolished homes in the east, and in their own country, they are still refugees. How many of them cannot find a flat at a humane price, either because it is easiest to make money on their own refugees too, or because in the advertisements they read: ‘Not for people with dogs or those from Donetsk’.

She recalls going to a village near Ternopil a long time ago, she was perhaps nine years old. Some old woman asked her in Surzhyk (a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian) why she did not speak Ukrainian. She regrets to this day that she did not ask the same thing.

It is important for the government and institutions to use Ukrainian, but why can you not think in whatever language you want? Why the pressure? It takes time.

PLN 17 per minute

Finally, everything has to be mixed together with the melted jelly, the biscuit filling and add the remaining biscuits so that nothing goes to waste.

She reads that the Ukrainians in Bakhmut are fighting so stubbornly as to systematically exhaust the Russian forces. Has anyone asked her and have they asked Kostya how much strength is enough for them? She would give anything for him to be far away from there. But she does not know how she could live on if he had said ‘no’ and refused to fight.

A boy from his unit, their mutual friend, did just that. A professional, they have served in the same border guard unit for fifteen years. Not long after his arrival, in January, he locks himself away and a couple of others in the basement at their base. He does not go out into position, he does not fight. Four boys are killed on the first day, while fourteen are wounded. Kostya tells Ira that their commander has made a lot of mistakes. They are moving him somewhere in Odessa, probably to make out he is smart there.

Ira is friends with the wife of the one who locked himself in the basement. She finds out that she was the one who asked him to refuse to continue to serve. Why can Kostya go and that one not? And now he is fighting both for himself and for him.

Kostia calls in the middle of February, now from the ambulance that is taking him from the base. Metal shrapnel pierces his forearm.

You’re injured, you can write an application for a transfer so as not to return to the front.

But it takes time: first an investigation, a check of readiness to continue fighting, and you also have to find work somewhere else, which is compatible with your position. Kostya is in hospital in Kharkiv for eight days. He does not write an application. He returns to Bakhmut. ‘What am I to do? Someone has to replace those who return from their positions. Don’t ask me at all about that one who hid in the basement. I don’t know anything about him and I don’t care.’ Ira wonders how quickly he will end up in court and where he will go afterwards.

After 2014, many go into the army because you can earn more than elsewhere, but no one expects there to be such a war. Everyone wants money, but not to fight. The basic salary after fifteen years of service is twenty-five thousand hryvnias, on top of which there is now a war allowance of thirteen thousand hryvnias, which, after conversion, gives a total of more or less four thousand, eight hundred zlotys. The government pays him an additional one hundred thousand hryvnias for every month at the front, which is twelve and a half thousand zlotys.

More or less 416 zlotys per day in hell. A minute of life in Bakhmut is worth 17 zlotys.

Days of pay are deducted for every day in hospital.

Dad

Now, the well-mixed thick mixture just needs to be poured into a mould, on the biscuit base, and put in the fridge for several hours.

Kostya knows a week in advance that he is going to the front, but tells Ira when he is on his way. Why add to her worries. Ira can sometimes see in the webcam that he is very tired. But he is rather more often angry than sad. At the mess, at the bosses, at their stupid decisions. Like that first day at the beginning of January, when the boys did not have to die at all. Ira likes to hear that Kostya is scared. She feels relieved when he tells her. All too rarely. She asks him to tell her what he feels. You have to be afraid in war; that is how it is supposed to be. It cannot be any other way, so that we can go back and get on with our lives.

The cake just has to coagulate now. And Kostya has to call. She still needs to wait for one phone call. She is slowly getting used to the fact that she will never hear from him again. Dad would call to ask if everything is okay, and he himself cannot wait to see his grandson blowing out the candles. When she argues with her husband, her father watches carefully and tells her himself not to be too angry for too long, because he is a good person.

Kostya calls from the headquarters of the border guard division on 24 February last year, at five o’clock in the morning. It has started. He tells her to buy tickets to Kharkiv for today for herself and Tioma. Two hours later, his voice can be heard on the phone again: ‘Give back the tickets, the Russians will be there shortly’. She sets off with the child to her brother’s house in Zabakhmutka, picking up a friend with her child along the way. Her parents, other brother with his wife and children show up. She thinks about what she has to do.

She goes back to her flat for a while with her father, takes some additional clothes for the child and something for herself for warmer days. She explains to her dad that she does not know what is going to happen, but trusts her husband, who knows best in this situation.

They have to get their child as far away from the war as possible. Dad cries.

They are still wandering around the city together, sorting something out. She is soaked from all this running around. When they move out, dad calls several times a day. In April, he and Ira’s mum leave for Ternopil (130 km from Lviv, 1,000 km from Bakhmut).

In May, she finds out that Dad has cancer. Ira returns to Ukraine for her father’s operation. She takes him to Poland in July. She travels around the city, learns about Warsaw at an express pace, makes phone calls, arranges a pesel number, transport, doctors, chemotherapy ports, test dates, translations, prescriptions and medicines. How should he suffer so terribly in a tiny flat with a beloved little grandchild? Ira finally finds a hospice. So he has somewhere to die. He will not make it there on time.

Maybe he should not have been brought over to Poland? Far away from her friends, of whom he and his mother have so many, to a foreign country. When he dies, Ira consoles herself: at least he could feel what a clean, normal hospital is, what respect of nurses is, without thousands of hryvnias that go to bribing doctors, and what a lack of contempt is. Shortly before his death, he asks her with the rest of his strength: ‘How do you say dochka in Polish?’ ‘Córka’ [daughter] Ira answers him. ‘It’s good that I have daughter,’she hears.

Five

The cake is ready. A big blue candle in the shape of a five made of Lego bricks fits perfectly. The phone rings early in the morning on the day of the kinder party. Kostya has returned from his position in the morning, after four days. He and his colleagues could not leave, they were waiting for permission and a signal that they were not surrounded. At around ten o’clock, nursery school children come to the Warsaw café, the party is just beginning. For a moment a bearded figure flashed before me on Ira’s phone – he can barely be seen, he’s lying in a dark room; I know it’s the basement in Bakhmut.

‘Can you see how I’ve dressed up?’ She smiles to her husband. I confirm that she looks lovely. Her eyes are glowing, the shadows from yesterday have disappeared.

Kostya is back in position before the last of the cake disappears from the refrigerator.

Post script

President Zelenski went to Bakhmut on 22 March. He listened to the battle report and decorated the bravest soldiers. Kostia did not meet him; he is in hospital again, having been wounded in the leg.

Filmoznawczyni z wykształcenia, redaktorka, autorka tekstów i reportaży.

Filmoznawczyni z wykształcenia, redaktorka, autorka tekstów i reportaży.

Komentarze