Here, even a teddy bear can carry a bomb. How to save the sick children of Kharkiv? [REPORT]

On the first day of the war, they pretended to the children that nothing had happened. When asked about the explosions, they said that it was a salute of honour. They called the barricaded windows a new game. In the end, they organized karaoke for them, stuck smiles on their faces, whereas inside they were trembling with fear

Powiedz nam, co myślisz o OKO.press! Weź udział w krótkiej, anonimowej ankiecie.

Przejdź do ankietyPublikujemy angielskie tłumaczenie tekstu Stasi Budzisz Tu nawet pluszowy miś może być miną pułapką. Jak ratować chore dzieci z Charkowa? [REPORTAŻ].

SOFIA wants to put an end to the war. She dreams of a Nerf, a toy automatic electric gun, because it can certainly handle the war. She left the war in Kharkiv, but here in Lublin she sometimes remembers it. She screams and cries in her sleep, but is unable to talk about it in the morning.

It happens that the war ‘visits’ her during the day. Sofia distrustfully looks up at the sky when she hears an airplane; she has goose bumps. When an ambulance’s, police car’s or fire engine’s siren sounds, she runs to Anna and falls into her arms. On New Year’s Eve, she was woken from her sleep by fireworks. ‘Anna, war, the war has come here! Save me!’ she shouted.

A song about Kharkiv

I visit them on the sixth floor of a Lublin hall of residence converted into a Ukrainian refugee centre. Anna goes to the kitchen to make some coffee. I stay with Sofia. She is nine years old; she has just come back from school and is finishing eating porridge. She watches me carefully from behind her coloured glasses. I shake her hand to greet her, but she does not let go of my finger.

‘I’m a bit shy of you,’ she says. ‘I’ll hold on to you for a while, is that okay?’

They have been living in Poland since 2022. They came in an evacuation train, in a special carriage where there were just eleven children with disabilities and caregivers. They have already somehow made themselves at home, they have even got a little used to it, but they cannot cope with the longing. Sofia keeps repeating that she wants to go home and sings a song about Kharkiv:

‘Eto lubimyj gorod Kharkiv,

eto lubimyj gorod nasz,

gorod kotoryj serdcem

ty nikogda nie predasz.’

[Here is the beloved city of Kharkiv,

here is our beloved city,

a city with a heart

you will never betray]

Anna knows they will not return too soon. They have nothing to return to.

Sofia wakes up to war

Anna could not sleep on the night of 23–24 February 2022. She was turning from side to side on the hospital bed and thinking about Sofia’s rehabilitation. They had just finished a two-week stay at the children’s palliative hospice at the 5th hospital in Kharkiv. Anna was happy that there were free beds and they could stay a few days longer. The rehabilitation was helping Sofia: she was talking more and better, becoming fitter.

The problems started when she turned three. First came the diagnosis – hydrocephalus. And soon afterwards – a brain tumour compressing the optic nerve. Operate, rehabilitate and pray.

‘And leave Slavyansk, because staying there with such a diagnosis meant condemning her to death,’ Anna recalls. ‘Then teach her to sit up, crawl and walk once again.’

Anna has known Sofia since she was born. She is her niece’s daughter. Her niece became pregnant by accident, for a few pennies, somewhere in a city sauna.

She was just nineteen years old, more raring to go out into the world than into nappies. Sofia was less than a year old when her mother relinquished her rights to her by notarial deed, handed her over to the care of her grandmother and set off to the bars of St. Petersburg in search of a better life.

‘The same as her mother, and my sister,’ says Anna. ‘A few years before Sofia was born, her drinking partners killed her, but she had also abandoned her daughters before that.

When Sofia fell ill, Anna gave up her job, packed her suitcase and took the girl to Kharkiv. Her biological mother only visited her in hospital once, after which she completely disappeared.

That night, it was not only Sofia’s matters that kept Anna awake at night. Russian troops were collecting on the borders and, although the media claimed that everything was under control, Anna could not sleep. She and the other mothers from the stay at the hospital reassured each other that

‘It’s not possible, Putin is not so crazy. Rashka will not go to Kharkiv after all.’

(Rashka. Russia. That is how Russia is referred to throughout the post-Soviet world. Diminutive, not completely serious, but with concern).

She got up before five o’clock, moments later she heard the first explosion. She acted like a machine. She had already been through this in 2014, when the Russians went into Donbas.

Get dressed.

Wake Sofia up.

Stay away from the windows.

Go downstairs.

Get between the walls.

She woke up the mothers in other wards and thanked God that she managed to extend her stay at the hospice, because the war would have found her on the eighth floor of the block of flats of the Saltivka housing estate, which the Russians had destroyed. Her flat has to be completely renovated after the attack.

Przeczytaj także:

Bombs and karaoke

We visit the hospice and Neurological and Psychiatric Hospital for Children No. 5 in Kharkiv in February, several days before the anniversary of Russia’s attack on Ukraine. The time is just after 4 p.m., all procedures have already ended, so Vladliena Viktorivna Salnikova, the medical director, and Tetyana Mikhailivna Prikhodko, the hospital’s chief physician, have more time to talk to us.

They have been operating since early 2018 and can accept twenty patients aged under eighteen at a time. They boast that they have wards which are accessible for people with disabilities, bathrooms with all conveniences, ramps, a lift and a rest area for parents.

‘Everything here is to a high standard, but we were not ready on 24 February,’ says Vladliena Viktorivna Salnikova. ‘We didn’t have a shelter or a generator that could handle the whole hospital. There were a few small ones, but they didn’t manage, and we didn’t know how to start them up. There was no man around to help, only a guard who was afraid of leaning out of his shelter.’

On the first day, they pretended to the children that nothing had happened.

When asked about the explosions, they said that it was a salute of honour. They called the barricaded windows a new game.

In the end, they organized karaoke for them, stuck smiles on their faces, whereas inside they were trembling with fear.

‘There were initially eighteen children here with various stages of disability, plus eighteen mothers and hospice staff,’ recalls Tetyana Mikhailivna. ‘We all crammed into the corridor, between the walls, as far away from the windows as possible. We thought it would last no more than a week. After all, we’re in the 21st century, so what war!’

There was no electricity, no water supply, no food.

A catering company supplied the hospital until 24 February, but when the Russians started firing, everything came to a standstill.

‘Tanks and armoured transport vehicles drive along the streets. It is not known who is who. Public transport isn’t working, you have to pay as much for a taxi ride as for an air ticket. Planes are flying overhead, while rockets are pounding the city like crazy. Shops and pharmacies are closed and, since the third day we have had sixty people with us and almost nothing to eat,’ recalls Tetyana Mikhailivna.

Three carrots

The mothers brought their other children, who were waiting at home, to the hospice. Nona, the mother of 13-year-old Dasha, a ward of the hospice, phoned, crying, begging for a place for her and her older son. A terrified babushka from the neighbourhood came with her dog and cat.

‘We wrote on Facebook that we needed help,’ says Tetyana Mikhailivna and opens a video on her phone. I see a man who walked several kilometres to them under heavy fire and brought food in a rucksack. I see him pull out a kilogram of rice, half a packet of pasta, salt, sugar, compote and chocolate. He says: ‘I didn’t have anything else.’

Tetyana Mikhailivna hides the phone in her white apron and wipes her wet eyes. So do I.

‘A neighbour from the block next door brought us a bag of frozen homemade pelmeni and two jars of jam.’

There was also an elderly man who brought three carrots and five potatoes. He wanted to share what he had.

‘They started distributing bread a few days later and volunteers with humanitarian aid also showed up. When they arrived, we threw our arms around their necks.

It was as if they were from a different world; if not for them, we would have died of starvation.’

Password: Diadiya Vanya

‘A missile struck the building next door. Shrapnel hit the hospital, the whole building trembled in its foundations. It was difficult to calm the children down,’ recalls Vladliena Viktorivna. ‘We decided to evacuate the patients.’

It was the middle of March, the hospital had neither electricity, water nor heating. However, communications appeared once and then disappeared for several hours. The health department in Kharkiv had already been bombed, it was difficult to contact any decision maker.

‘Well and nobody wanted to take responsibility,’ says Tetyana Mikhailivna. ‘We made all decisions on our own. I managed to contact the department. I said the situation was critical and we had now run out of courage. I asked for permission to evacuate.’

They said ‘fine, Tetyana Mikhailivna, evacuate, but we don’t know how to help you.’

‘I managed to obtain the contact details for the head of the SBU. I said we have to evacuate by yesterday and, if necessary, I can kneel before him, as long as he helps us.

He gave us two hours to prepare to travel. The Greek Orthodox Church organized transport to the railway station, gave medicines and packed lunches.

Before leaving, the directors invited everyone to a meal. They put out fruit, sweets and a bottle of champagne. Everyone was crying.

We rode in a convoy of ten buses, one after another,’ recalls Tetyana Mikhailivna.

‘The mothers didn’t know it, but we agreed that if a missile hit one, the remainder would drive on.’

Anna recalls that there was one explosion just behind the convoy and another next to it.

‘But the worst thing was what we saw through the windows of the marshrutkas. Up to 17 March, we hadn’t even peered out of the hospice, while communications were poor, so photos and videos were loading poorly. And here we suddenly see a demolished city. Empty and dark. It then occurred to me that what had happened eight years earlier in Slovyansk was just a bit of fun compared to what the Russians were doing in Kharkiv.

The station was besieged by a panicking crowd. A separate carriage was prepared for the eleven children, caregivers, families and medical staff. It stood on a siding so as not to irritate those for whom there were insufficient seats on the evacuation train.’

‘Everything was closed, wild crowds all around, panic,’ recalls Tetyana Mikhailivna. ‘I finally managed to get in touch with the right person, and in response to the password “Diadiya Vanya”, they packed us into a carriage, locked us in, covered the windows and told us to wait.’

This war is because of you!

They moved off after four hours; no one knew where to.

‘The fear was paralyzing,’ recalls Nona, who I also met at the Lublin hall of residence. ‘I rode with Dasha and my older son.’ Dasha fortunately understood little of all this, but Bohdan was tense, although he pretended to be tough.

They first told them that they would leave everyone in Poltava, and from there everyone has to cope on their own.

‘And how are you supposed to cope?’ asks Nona. ‘A child with palsy who doesn’t speak and can hardly walk. You have some luggage, some money, but what next? Everything is uncertain and scary.’ We finally arrived in Kyiv. We waited there for several hours, in uncertainty. You don’t know if they will hit the station or not. A tragedy was already in progress in Bucha, although we could not even imagine its scale. There was no longer a bridge on the River Irpin. No one informed us about anything.

‘When you have a healthy child, you’re also afraid, but you can’t explain or reassure a child with a disability so easily,’ says Anna.

They finally set off and arrived in Lviv after thirty hours. Hospital beds were waiting for them as were the hateful stares of the compatriots from western Ukraine. Anna and Nona were told to their faces:

‘It’s so good for you!’, ‘You’ve come here!’, ‘It’s all your fault!’, ‘This war is because of you!’,

‘We prayed out our Lviv, but God punished you!’

‘The bedsits in Lviv were going for 40,000 hryvnias (4,500 zlotys) each,’ Nona is annoyed. ‘They were renting out their flats to Ukrainians from the east of the country at these prices, and themselves going to Poland to defraud money for refugees.’

‘That’s just great,’ comments Anna. ‘They made money on us in Ukraine, and on you in Poland. I’m ashamed of them before the Poles.’

Our own

After four days, they provided a bus to take the whole of the Kharkiv group to Poland. The hospital sent two nurses from Lviv with them.

‘They were scaring us about the Poles all the way,’ says Nona. ‘That children with disabilities are not treated in Poland. That they don’t fight for those children’s lives. That we are taking them to certain death.’

‘And that you will spit on us because we speak Russian, and you hate the Ruskies,’ says Anna. ‘I think everyone was afraid of you on that bus.

We stood at the border for five hours. Everyone fearing for the fate of their child in a foreign country.’

‘But in Poland, we experienced a shock,’ Anna recalls with tears in her eyes. ‘Children with the most severe disabilities were immediately taken away by helicopter, while professional medical transport was waiting for the others. They took us to a rehabilitation centre in Lublin.’

‘We arrived late, around 10 pm,’ says Nona. ‘And then another shock. The entire staff and the whole of the centre’s management were waiting for us. A hot meal had already been prepared, as were beds and bathrooms. They checked the condition of the children and gave them two days to rest after the difficult journey. Then, they handled the formalities and diagnoses. And we were so scared because of the stories of the nurses from Lviv.’

‘I don’t know why the west of Ukraine hates us so much. Sometimes, I think to myself, should I really judge Rashka, if my own people treat me like a traitor,’ says Anna.

Teddy bomb

On 17 March, after taking the people to the railway station, Tetyana Mikhailivna went home for the first time since Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Only for a few hours; she then locked herself in the hospice again for almost two months.

They started to build a shelter. They were digging in the ground under the building, deepening the space under the walls. The Kharkiv cardboard factory made them cardboard beds and stools. They were light, so everyone could move them to safety in the event of an air raid alert.

‘We asked for help wherever we could,’ says Tetyana Mikhailivna. ‘The U.S. sent us nine shipments of medicine, but only two arrived; even so, this was still something. UNICEF donated a large generator to us, so we are now secured. We also have supplies of water.

‘Well, and we finally have a shelter,’ adds Vladliena Viktorivna.

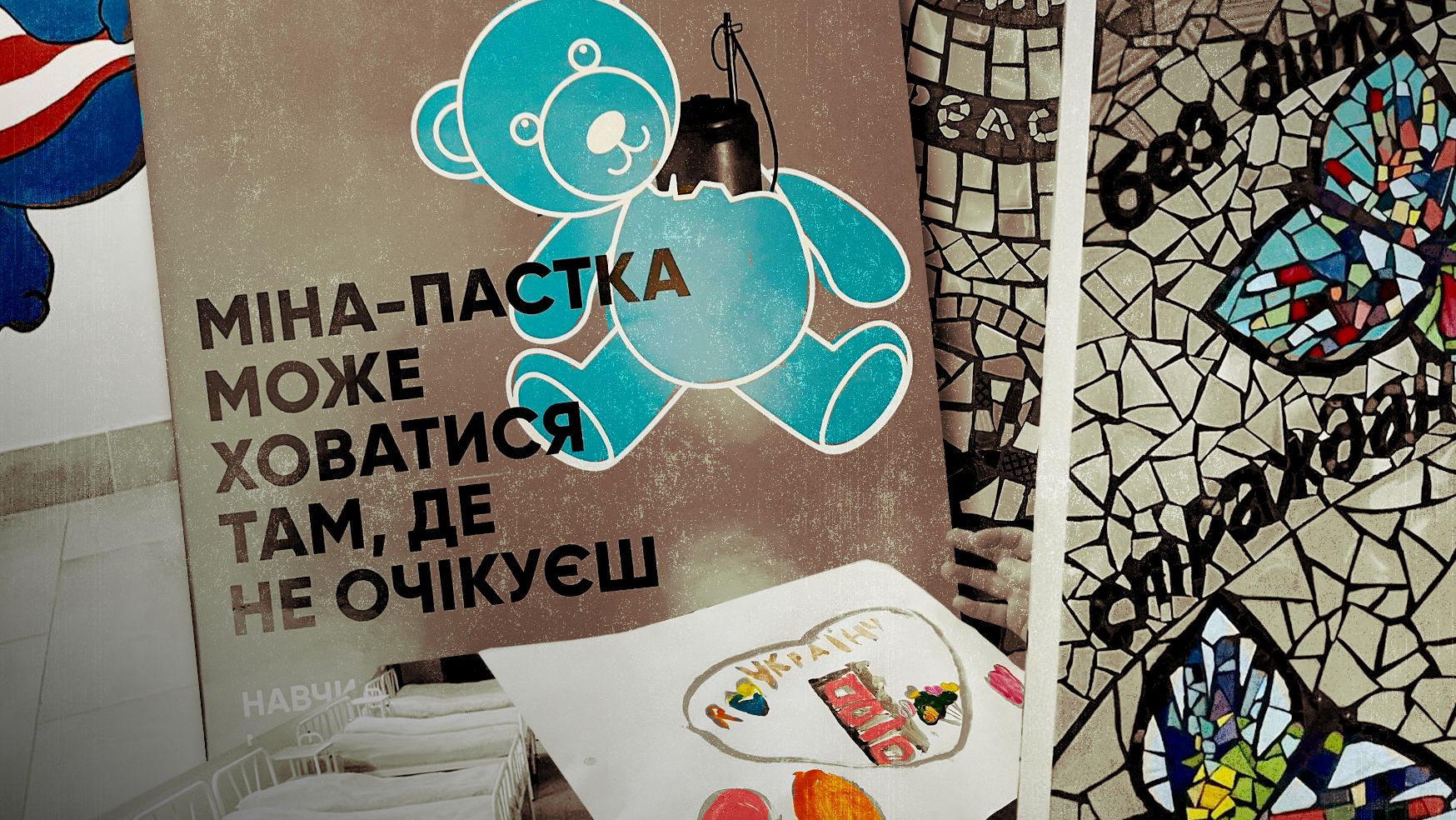

We go down to the basement on a narrow staircase. The main hall has colourful walls, with elephants laughing, flamingos strutting and mice waving their fingers. If it weren’t for the low ceiling, the lack of windows and the warning poster about the teddy bomb (just an ordinary teddy, but when you pick it up, you are blown into the air), everything would look like an ordinary hospital ward.

Nothing is unambiguous in war, so everyone needs to be sensitized, parents and especially children. Teach them mistrust, explain who the enemy is, show the dangers. Do not pick up a teddy bear lying in the street. Does it have a blinking diode, some wires? Call 101.

‘We managed to dig out a shelter in August, so now we spend every night here, because there is more shelling at night,’ says Vladliena Viktorivna. ‘We can also go down to the shelter during the day, during an air raid warning, but it is up to the parents to decide.’

They have had increasingly more work since last February. They aren’t even thinking about leaving Ukraine.

‘There is increasingly more depression, epileptic fits, wetting not only at night,’ says Tetiana Mikhailivna. ‘The reaction of some children to the sound of a siren is that they hide under the table, others scream so much that there is no way of calming them down. The war can no longer be hidden from them, although not all of them understand what that means. War is an abstract concept to them. This can be seen on their drawings.

We are standing in the room where art therapy classes are most often held. The windows are no longer covered with plywood, but firmly covered with adhesive tape so that the glass will not fall out and hurt anyone if they are hit. Children’s pictures are hanging from them. Airplanes are dropping bombs, there are tanks, destroyed blocks of flats. There are also Ukrainian flags and teddy-bombs.

Shortly before the war, students of the Academy of Fine Arts placed a mosaic on two pillars of the art therapy room. They wrote on it ‘for peace’.

Son turned grey

Anna and Nona are learning to be patient in Poland. They have to wait for everything: for benefits, for examinations, for their return home. Nona’s 16-year-old son turned grey and quite recently admitted to his mother that he had never been so afraid in his life.

‘If it weren’t for Dashka, I would certainly not be going anywhere,’ says Nona. ‘I’m living out of my suitcases, for the time being. I’m not planning my life here at all. I couldn’t do that. I want to go home. It doesn’t matter what it will be like there after the war. Home is home.

‘I also feel like I’m staying at someone’s house as a guest,’ says Anna. ‘I’m not living at home, because I’m here for Sofia. Such a form of survival. I wouldn’t have left if she weren’t a child with a disability.

I did not flee from Slavyansk in 2014, even though my child was fourteen years old. Now, I’m 47 years old and feel like an old woman. Donbas added 10 years to my age, the situation with Sofia another ten, and I think that what happened after 24 February added 20 more.

Too much for one person. Too much.

Sofia went to the first grade of Special School No. 53 for Mentally Handicapped Children of a Moderate and Severe Degree, where she is learning Polish. I try to talk to her. She understands everything, but answers me in Russian. When asked why, she replies: ‘well, because I was born there’.

Somewhere between playing and rehabilitation she misses Kharkiv and sings to herself:

‘eto lubimyj gorod Charkow,

eto lubimyj gorod nasz...’

[Here is the beloved city of Kharkiv,

here is our beloved city...]

‘We still have to endure,’ Anna says to Sofia. We still have to.’

The text was written in cooperation with Stanislav Brudnoch of the HumanDoc Foundation. I would like to thank Tetiana Grida, a psychologist from Kharkiv, for her help.

Stasia Budzisz, tłumaczka języka rosyjskiego i dziennikarka współpracująca z "Przekrojem" i "Krytyką Polityczną". Specjalizuje się w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej. Jest autorką książki reporterskiej "Pokazucha. Na gruzińskich zasadach" (Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 2019).

Stasia Budzisz, tłumaczka języka rosyjskiego i dziennikarka współpracująca z "Przekrojem" i "Krytyką Polityczną". Specjalizuje się w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej. Jest autorką książki reporterskiej "Pokazucha. Na gruzińskich zasadach" (Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 2019).

Komentarze