PLN 1800 per month for a bed in a communal hall? A loud NO in OKO.press’s Ukrainian debate

How is a Ukrainian mother with two small children vegetating in a centre to pay PLN 1800 for her stay and simultaneously earn money to support her family? The government’s idea is unwise and cruel. This is the first conclusion in OKO.press’s Ukrainian debate

Powiedz nam, co myślisz o OKO.press! Weź udział w krótkiej, anonimowej ankiecie.

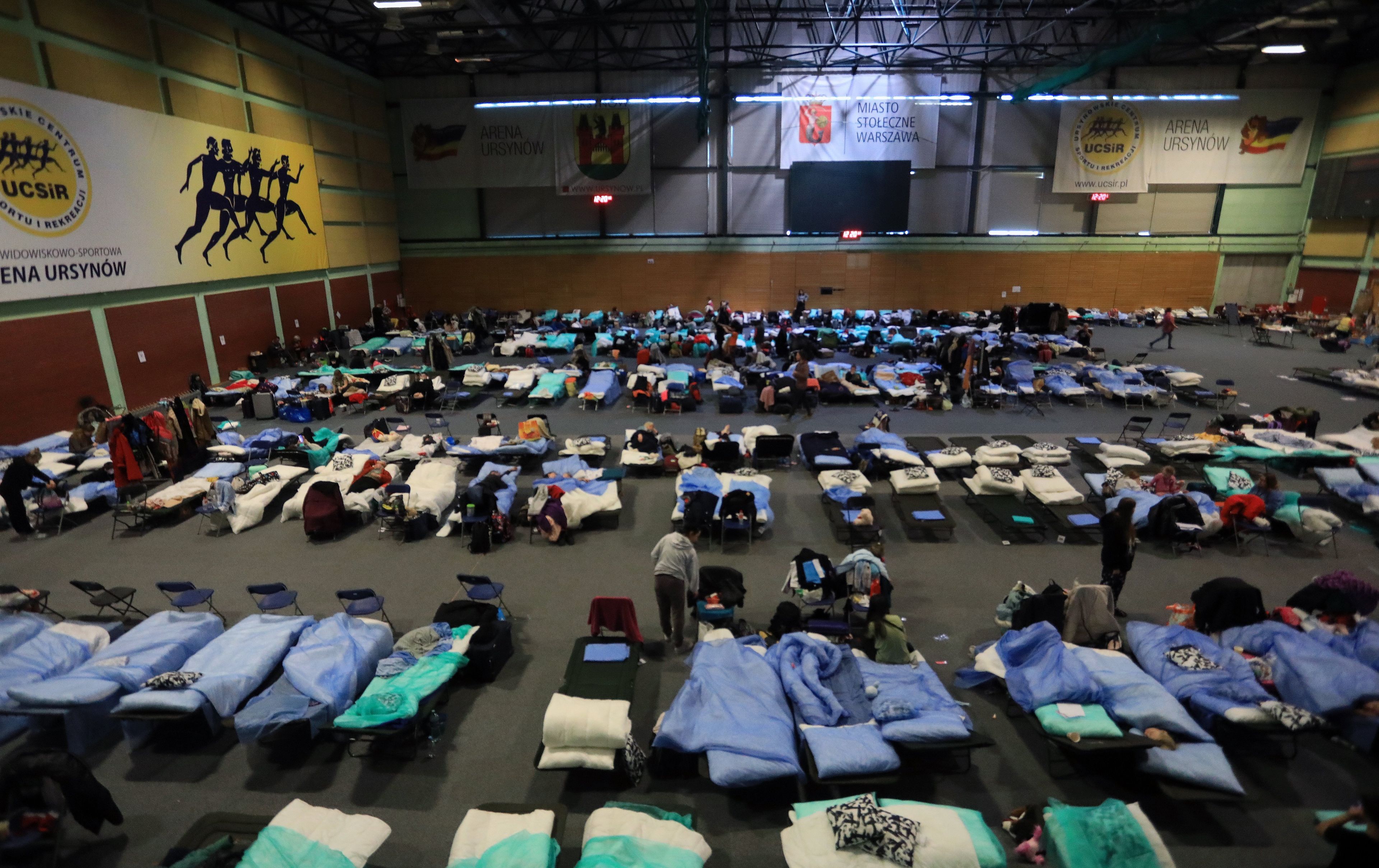

Przejdź do ankietyIn the GOVERNMENT’s proposal of the amendment to the Act on aid to the citizens of Ukraine (as usual, the feminine form of the expression in Polish is missing, even though the issue primarily applies to women and children), from February 2023, refugees are to pay for their stay in centres referred to in bureaucratic talk as „places of collective accommodation”. And it is not a small amount at all — as much as PLN 1,800 per month per person (with exceptions – see below).

This solution aroused particular opposition and even indignation during the Polish-Ukrainian debate organized by OKO.press on 18 November 2022 in Warsaw’s Powszechny Theatre in our ‘We are here together’ campaign.

The record of the whole of the debate can be found below (worth watching):

More about the „We are here together” debate and campaign at the end of this article. But first, let us give the floor to Stanislav.

Stanislav, namely living on the edge

Stanislav has just turned 70. He arrived with his wife in April 2022 from Zaporizhzhia, the capital of the oblast on the Dnieper River, in the south-eastern part of Ukraine, right next to Europe’s largest nuclear power plant (currently under Russian control). Volunteers at Kraków railway station directed them to the disused Plaza shopping centre, which, until August, had been a shelter for approximately 400 people. They lived there for two days, experiencing the difficulties of „communal accommodation”.

„It was difficult. 50 beds laid out in one hall. We are at such an age that ... my wife, the noise. Panimajetie? [Eng.: Do you understand?]”, he asks in Russian, and I nod that I understand.

Stanislav returned to the station asking for different accommodation. He succeeded, they got a room in the AGH hall of residence at ul. Budryka, where they have been living to date. Free of charge.

„Everything is there, a kettle, even a microwave oven...”, says Stanislav. He keeps checking on how many missiles are falling on his Zaporizhzhia. Fourteen people were killed on 10 October, including a child; 89 were injured.

They live off Ukrainian pensions, which are paid into their account. They receive the minimum amount for people in their 70s, 3,000 hryvnia each, a total of 730 zlotys.

The grounds for their survival are aid centres, where they receive clothes, food and hygiene products and some medicines. They get them? Perhaps in the past, but now it is rather a matter of „acquiring”.

In the initial months of the war, the centres were full of goods, serving hundreds of people every day. Now, every centre has limits, they are rationing the aid. Stanislav knows all the points, the opening times and the limits, by heart; he recites the names, the addresses and the product ranges.

Some centres only let people come once a month. „They have our names written down in tables. I came on Wednesday, they tell me: you were here yesterday, you won’t get any clothes. I simply made a mistake. But I returned with shampoo”.

His daughter and her family are still in Ukraine. „But if such shelling continues, she will come to us”, says Stanislav, only he does not know how they will manage.

„And now there are also these charges”, this is what he and his wife fear the most. They heard that refugees are supposed to pay 60 zlotys a day per person for their accommodation. He calculated for himself that they would be paying 3600 zlotys, or 30,000 hryvnias.

The amount overwhelms him: „Where are we to get so much money from?”

I calm him down, saying that, as pensioners, they will be exempt from the charges, but he doesn’t really believe me. He heard that only children will not pay.

This is another of the hundreds of refugee stories OKO.press’s journalists had heard during the nine months of war in Ukraine. The problem of where to live is becoming increasingly dramatic.

Mothers with children, the elderly and people with disabilities and their carers are a special group. They cannot work full-time or even at all. Tania from near Odessa, about whom we wrote, will not go to work because her son, Nikita, has spastic quadriplegic paralysis, microcephaly and epilepsy. Someone needs to be with him all the time.

Even if people from Ukraine manage to find work, it is difficult for them to rent a flat, because the stigma of being a ‘refugee’ is an obstacle. Poles are afraid to rent, even when they are shown a certificate of employment. After all, in general, they hang up when they hear a Ukrainian accent.

As sociologist Oleksandra Dejneko of Kharkiv National University, who currently works at the Norwegian Oslo Metropolitan University, pointed out during the Warsaw debate ‘We are here together’, war emigration from Ukraine is atypical. More than half have degrees, speak foreign languages, usually not poor at all, and easily adapt in any country.

But even they cannot find accommodation. The only option for Stanislav and his wife is a free place. However, there are increasingly fewer of these, while a significant proportion of refugee families would have to pay for them.

Debate at the Powszechny Theatre, 18 November 2022 Panel 1. From the right: Dominik Owczarek, Myroslava Keryk, Magdalena Czarzyńska-Jachim, as well as moderators Krystyna Garbicz and Piotr Pacewicz – Photo Mikołaj Maluchnik/OKO.press

Government is relying on ‘activating Ukrainian citizens’

The government wants the refugees to pay for their stay in „places of collective accommodation” from March 2023. If they are in Poland for longer than 120 days, they are to cover 50% of the cost (no more than PLN 40 per day). And if they are staying longer than 180 days – 75% of the costs (to a maximum of PLN 60 per day). The bill was prepared by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration.

Children, pregnant women, single parents with three or more children, pensioners and anyone who „is in a difficult situation in life which prevents them from contributing to the costs of the aid” are to be exempted from the charges.

The justification of the bill refers to „the introduction of the participation of Ukrainian citizens in the costs of board and lodging”, which has the „objective of sanctioning the practice of subsidizing the service of board and lodging by Ukrainian citizens and activating Ukrainian citizens staying at collective accommodation centres”.

In the so-called impact assessment of the regulation, the government answers the question of how the problem is solved in OECD/EU countries. The question is all the more important as we have not managed to find a similar situation in which a country hosting refugees in communal centres takes money from them for that. However, the response from the originators is more than perfunctory:

„The bill is incidental in nature. The objective of the bill is to regulate certain matters related to the mass entry into the Republic of Poland of Ukrainian citizens who have left Ukraine in connection with the armed conflict”. And that is all.

The government's bill has not yet been submitted to the Sejm; it is being assessed by the voivods and the Joint Commission of the Government and Local Government. However, Professor Maciej Duszczyk of the Centre for Migration Research at the University of Warsaw already likes it. He presented two arguments in DGP in October 2022:

- „the situation of Poles needs to be equalized with that of the Ukrainians, a Pole excluded from housing must not be treated worse than a Ukrainian in the same situation”;

- „refugees must not be allowed to become dependent on state aid. If this is not done, we will have acquired helplessness among refugees and political exploitation of this topic by right-wing groups, who will say that Poles cannot afford to pay for electricity while the Ukrainians are living for free in a three-star hotel”.

Advocates of equal treatment can be asked if homeless Poles pay 1800 zlotys for a bed in a collective hall. And whether the idea of ‘activation’ is an appropriate reaction to the difficulties of the hardest-hit, most helpless group of refugees. Is this supposed to be a cure for acquired helplessness? The mere announcement of the rates as for a cheap hotel? The cheapest hotel room in Radom costs about PLN 100 while in Skarżysko-Kamienna it is PLN 120, whereas, in smaller towns, a small flat can be rented with a kitchen, bathroom and free wi-fi for PLN 150-200, but they can accommodate 2-3 people.

Anyone who was able to, activated themselves

There are around 80,000 Ukrainian men and women in collective accommodation. These are places managed by both the public administration and NGOs or private entities (the map of places offering aid to refugees can be found at mapujpomoc.pl).

A significant proportion of people who live in such centres are children, as well as the elderly and the sick, which means that ‘participation in the costs’ would not bring big money. Assuming that one in three people are to pay, at an average of PLN 50 per day, we can calculate that the budget would ‘earn’ no more than half a billion.

If it were to earn anything at all, because some of the people who would not receive relief would simply have to leave the centre. Leaving a problem for them on their own, as well as for the local authorities and the state administration.

How is a Ukrainian mother with children aged two and four to pay PLN 1800 for her stay and simultaneously earn money to support her family?

The argument about mobilization does not take into account the fact that it is the refugees who are in the greatest need who end up in the centres. And simultaneously, the least resourceful ones, who were unable to benefit from contacts with Ukrainians who are already in Poland, who do not have any contacts or support from family and friends, who are in the worst situation. It is also the people who arrived in the summer months who have had several months of war behind them, unlike the people who arrived, for instance, in March, who „only” experienced the first shock.

They are staying in the centres because they could not cope with starting to live independently. Now, the officials are to decide on their fate based on the discretionary criterion of the „difficult living situation preventing them from participating in the costs of the aid”.

We tried to persuade the supporters of the „mobilization theory” to confront reality: nobody stays in such a centre given the choice.

Debate at the Powszechny Theatre, 18 November 2022. Panel 2. From the right: Michał Bilewicz, Krystyna Potapenko and Aleksandra Hnatiuk. Photo Mikołaj Maluchnik/OKO.press.

A centre is a last resort

Life in such centres means living in difficult conditions on an everyday basis – in a small space, crowded, queuing for a shared bathroom, for a place to prepare food for themselves and even for the use of an electricity socket. People in the centres are vulnerable to sickness, especially during the coronavirus pandemic. People who are seriously ill or have undergone surgery should not be accommodated in them, whereas Krystyna Garbicz wrote about such cases in OKO.press).

How are children supposed to learn – remotely, in their Ukrainian school – in the conditions of a centre, when they are often lacking a desk, not to mention silence? Anyone who has seen how difficult it is for a ten-year-old to take part in an online lesson will understand what the difficulty involves: they need to focus and have a minimum level of intimacy so that no-one can hear the child answering the teacher’s questions.

„Collective accommodation” isolates refugees from the rest of society and makes the integration process difficult.

The government arbitrarily assumes that 120 days for starting to live independently after fleeing from a country at war is enough time (more on that here), but the point is that those for whom it was enough are not stuck in the centres. The government’s idea is actually an attempt to liquidate this form of support, but it could mean that some refugees will be threatened with homelessness.

We were looking for answers during OKO.press’s Ukrainian debate on how to solve the problem of places to live for 1,521,000 refugees after 24 February (according to UNHCR data of 29 November 2022 – that is how many PESEL numbers were issued). This means that 19.3% of all the people who left Ukraine or fled/were resettled in Russia are staying in Poland.

There are many more Ukrainians in Poland than one and a half million, because, according to the Central Statistical Office’s estimates, there were already more than 1.3 million Ukrainians in Poland in 2020, mostly migrant workers. It is not known, however, how many of these people have returned (e.g. to fight in defence of Ukraine), how many have moved on to the West, and how many have taken advantage of the ability to obtain a PESEL number. It is also not known how many people are staying in Poland without a PESEL number.

In the next episodes of the series, we will continue to address the problems of housing, as well as work and education of Ukrainian children.

OKO.press’s debate – mistakes and absurdities in the government policy

Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, namely since 24 February 2022, we have been reporting on the fate of the refugees who have fled the country from the war to save themselves and their families. We are continuously reporting on events from the frontline, analysing Russian propaganda, but also intervening whenever necessary in the affairs of Ukrainians who are trying to live, work and study in Poland.

We point out the mistakes made by the State, write up the declining wave of civil aid to Ukrainian families and analyse the challenges encountered by more than 2.0 million war refugees and others during their stay in Poland. We consider what can be done to make the country to which they have fled a safe haven for the duration of the war or their new home. To help them survive and, if they so wish, to start a new life here, together with us.

The Polish-Ukrainian debate entitled „We are here together”, which OKO.press organized for 18 November 2022 at the Powszechny Theatre, showed us clearly how much needs to be done. Its participants of both nationalities from social organizations, local governments and universities tried to define the difficulties the refugees are facing and to look for solutions.

This was structured into several fundamental problems and sometimes absurdities, harmful laws and bad state policies.

We will discuss them one by one in the hope that they will be clarified and developed by Ukrainian and Polish organizations, specialists and the public.

This is a kind of intervention text. We will develop and supplement each of the threads – describing concrete stories of Ukrainians, talking to experts, and sometimes looking for solutions applied around the world, including even – horror of horrors – in Germany.

We are holding the campaign entitled: WE ARE HERE TOGETHER. The goodwill and ability to help Ukrainian families who, having escaped from Russian aggression, are trying to live, work and study in Poland, are slowly running out. The State no longer supports Poles who take in refugees. It is time to re-establish relations and look for solutions. In OKO.press, we want to write up the stories of the visitors from Ukraine, to hear them from you. We are also waiting for letters from Polish employers, hosts, anyone who wants to write a comment or submit an idea. Write to [email protected].

The „We are here together” debate at the Powszechny Theatre in Warsaw was introduced on 18 November 2022 by:

- Oleksandra Deineko — associate professor of the Faculty of Sociology at the V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Urban and Regional Studies, Oslo Metropolitan University. One of the founders of the research network on Ukraine in Norway – Ukrainett. Oleksandra’s research interests are social cohesion, migration and Ukrainian studies. She researches the experience of Ukrainian refugees in Norway;

- Jakub Tylman — teacher of arts, music and Polish as a foreign language at the preparatory classes for refugees at the Knights of the Order of the Smile Public Elementary School in Śrem, this year’s winner of the prestigious Irena Sendler ‘Repairing the World’ Award for teachers;

The first panel („living”) consisted of:

- Magdalena Czarzyńska-Jachim — Deputy Mayor of Sopot, a city that has developed a system of support for refugees from Ukraine, member of the Standing Committee on Equality at the Council of European Municipalities and Regions, Chair of the Human Rights and Equal Treatment Committee of the Association of Polish Cities, originator of the ‘Sopot Women’s Meetings’, namely debates about the most important issues from the point of view of women (interview in OKO.press);

- Myroslava Keryk — historian, sociologist, expert on the migration of Ukrainians to Poland. President of the Board of the ‘Our Choice’ Foundation and co-founder of the Ukrainian House in Warsaw, editor-in-chief of the monthly magazine ‘Nash Vybir’;

- Dominik Owczarek — Director of the Social Policy Programme at the Institute of Public Affairs, specializes in labour market and social dialogue issues, including the situation of migrants on the labour market (he has repeatedly made statements to OKO.press, most recently here).

The second panel’s („spiritual”) guests were:

- Professor Michał Bilewicz — head of the Centre for Research on Prejudice at the University of Warsaw (he has repeatedly made statements to OKO.press);

- Dr Hab. Aleksandra Hnatiuk — Ukrainianist, translator, professor at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and the University of Warsaw, vice-president of the Ukrainian PEN Club, awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (interview in OKO.press);

- Krystyna Potapenko — lawyer, poet, translator, volunteer, coordinator of international projects, specialist in Polish-Ukrainian cooperation.

The debate was moderated by OKO.press journalists: Krystyna Garbicz, Piotr Pacewicz, Agata Kowalska and Agata Szczęśniak

Dziennikarka, absolwentka Filologii Polskiej na Uniwersytecie im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, studiowała też nauki humanistyczne i społeczne na Sorbonie IV w Paryżu (Université Paris Sorbonne IV). Wcześniej pisała dla „Gazety Wyborczej” i Wirtualnej Polski.

Dziennikarka, absolwentka Filologii Polskiej na Uniwersytecie im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, studiowała też nauki humanistyczne i społeczne na Sorbonie IV w Paryżu (Université Paris Sorbonne IV). Wcześniej pisała dla „Gazety Wyborczej” i Wirtualnej Polski.

Jest dziennikarką, reporterką. Ukończyła studia dziennikarskie na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim. Pisała na portalu dla Ukraińców w Krakowie — UAinKraków.pl oraz do charkowskiego Gwara Media. W OKO.press pisze o wojnie Rosji przeciwko Ukrainie oraz jej skutkach, codzienności wojennej Ukraińców. Opisuje również wyzwania ukraińskich uchodźców w Polsce, np. związane z edukacją dzieci z Ukrainy w polskich szkołach. Od czasu do czasu uczestniczy w debatach oraz wydarzeniach poświęconych tematowi wojny w Ukrainie.

Jest dziennikarką, reporterką. Ukończyła studia dziennikarskie na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim. Pisała na portalu dla Ukraińców w Krakowie — UAinKraków.pl oraz do charkowskiego Gwara Media. W OKO.press pisze o wojnie Rosji przeciwko Ukrainie oraz jej skutkach, codzienności wojennej Ukraińców. Opisuje również wyzwania ukraińskich uchodźców w Polsce, np. związane z edukacją dzieci z Ukrainy w polskich szkołach. Od czasu do czasu uczestniczy w debatach oraz wydarzeniach poświęconych tematowi wojny w Ukrainie.

Założyciel i redaktor naczelny OKO.press (2016-2024), od czerwca 2024 redaktor i prezes zarządu Fundacji Ośrodek Kontroli Obywatelskiej OKO. Redaktor podziemnego „Tygodnika Mazowsze” (1982–1989), przy Okrągłym Stole sekretarz Bronisława Geremka. Współzakładał „Wyborczą”, jej wicenaczelny (1995–2010). Współtworzył akcje: „Rodzić po ludzku”, „Szkoła z klasą”, „Polska biega”. Autor książek "Psychologiczna analiza rewolucji społecznej", "Zakazane miłości. Seksualność i inne tabu" (z Martą Konarzewską); "Pociąg osobowy".

Założyciel i redaktor naczelny OKO.press (2016-2024), od czerwca 2024 redaktor i prezes zarządu Fundacji Ośrodek Kontroli Obywatelskiej OKO. Redaktor podziemnego „Tygodnika Mazowsze” (1982–1989), przy Okrągłym Stole sekretarz Bronisława Geremka. Współzakładał „Wyborczą”, jej wicenaczelny (1995–2010). Współtworzył akcje: „Rodzić po ludzku”, „Szkoła z klasą”, „Polska biega”. Autor książek "Psychologiczna analiza rewolucji społecznej", "Zakazane miłości. Seksualność i inne tabu" (z Martą Konarzewską); "Pociąg osobowy".

Komentarze